Psychopathologies

and cultural factors:

some

neo-evolutionist perspectives

Fabio

Petrelli* Roberto Verolini* Larissa Venturi**

*Dipartimento

di Scienze Igienistiche e Sanitarie-Ambientali,

Università degli Studi di Camerino

**Dipartimento

di Istituzioni Politiche e Scienze Sociali,

Università degli Studi Roma Tre

In the recent Neuroscienze ed evoluzionismo per una concezione olistica delle

psicopatologie e dei disturbi della personalità[1] we present a

detailed analysis of the influent factors that, proceeding from specific cultural

“constellations”, could lead up to typical structures of personality and social

behavior, driving dynamics of psych conditioning and exerting a weighty influence

over the individual knowledge capacity and over all the advanced expressions

involving human brain. In that work we follow the direction of search previously

suggested in Metamorfosi della Ragione: esegesi evoluzionistico psicosociologica

di Genesi 1,3 ed implicazioni bioetiche[2] and in Il Dio laico: caos

e libertà[3], where we set a formal division of the sacred dimension

in two big classes: “theoethotomies” as social structures

based on a marked ethical role of divinity, and “religions”[4]

as metaphysical systems infused with a non- moral divinity.

In our essay we discuss a revision of the space where the environment modelling

action and conditioning potentialities became operating. In fact, even though

we do not reject the physical and biological foundation of genetic causes of

psychic processes, concerning the species Homo s. sapiens[5], new theoretical

proposals from neuroscience are upsetting the reference points, by tracing out

a new explanatory pattern in which brain development cannot be intended outside

the structural contribution of external environment and learning process[6].

These factors “carve” human brain from an anatomic point of view, by selecting

and fixing connections among different groups of neurons. More specifically,

according to the evolutionist approach, conscience emerges as essential consequence

of cultural environment influence on individual senses, where psychic experiences

are modeled. Therefore this new outline of conscience markedly includes that

sphere of psychical experience where typical semantic values are expressed:

ideas, language, cultural elements transmitted and acknowledged by the group,

emotional constituents, spiritual and philosophic perspectives.

Our distinction between “theoethotomies” and “religions”

allows to describe a specific correlation between theological models and psycho-cultural

conditioning, and gives us a key of interpretation quickly attested by ethnological

empiric data[7]. Since the “Self” is structured as an expression, efficient

from the point of view of evolution, of external cultural and biological reality,

human brain and nervous system keep a psychic mark of that reality. Lots of

psychical dynamics are subordinated to the social expression of typical pools

of values which address individual development, just as characters working as

the ideal reference mark for the growth itinerary of an individual inside the

group.

As human cultures analysis shows that they are structured around some specific

ethical coordinate, the distinction we propose between “theoethotomies”

and “religions” gives us a classification of cultures

that follows a dichotomous way[8]. We can draw two antithetic psychical dynamics

that emerge from a comparison between theoethotomistic and religious models.

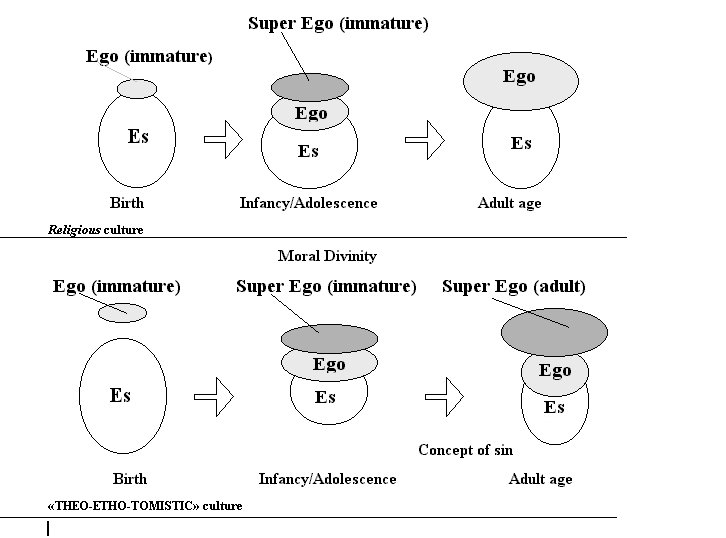

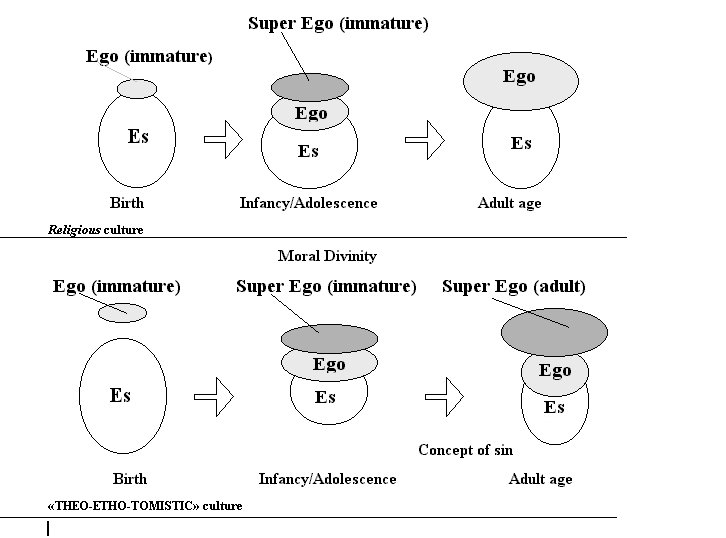

A first distinction refers to the hypertrophied development of Super Ego, a

consequence of the strong ethical and moral individual subjection towards the

sphere of the Sacred; in this direction, we advance a first conclusion: where

a full individual identification with the ideal of the Self is possible – i.

e. in the religious systems –, the conditions of an objective alienation from

the ontological perfection that characterizes the theoethotomistic cultures

tend to disappear.

If we consider also other characters, different human cultures can be arranged

according three rising levels of aggressiveness, in a diagram re-proposing the

well-known classification in classes A,B,C outlined by Fromm in Human Aggressiveness

Anatomy[9]. From the three classes analysis, tied to constellations of

typical factors, a positive correlation emerges with the appropriate theological

model: religious for the class A, theoethotomistic for B,

anti-religious for C.

In this context we set out in a new perspective some important questions emerged

in ethno- psychoanalytic and ethno-psychiatric research. We finally provide

a new interpretation of the term “psychopathology”, that goes beyond all those

expressions representing deviating or marginal elements from a standardized

interpretation of a “correct” experience of faith, traditionally considered

as “positive” and “orthodox” expression of religiosity. Our interpretation identifies

a “sane” religiosity only in determined faith contexts (religious) and looks

at the theoethotomistic models as pathologic forms of faith.

| |

Express

type of faith |

Concept

of sin (extensive) |

Ideal

of Ego |

Authoritative

patriarchal sex-repressive complex |

Attitude

in front of sex |

Private

ownership development |

| Class A |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Zuni |

Religious |

No |

Apollonian |

No |

Positive |

Scarce |

|

Arapesh

|

Religious |

No |

Mild

and dignified |

No |

Positive |

Scarce |

|

Aranda

|

Religious |

No |

Libertarian |

No |

Positive |

Scarce |

|

Semang |

Religious |

No |

Mild

and moral |

No |

Positive |

Scarce |

|

Class

B |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Manus |

Theoethot. |

Yes |

|

Yes |

Negative |

Strong |

|

Samoa |

Theoethot. |

No |

|

* |

Free

positive |

|

|

Inca

|

Theoethot. |

Yes |

|

Strong |

Religious

chastity |

* |

|

Catholic |

Theoethot. |

Yes |

Competitive

inhibitory |

Strong |

Negative |

Yes

(principle) |

|

Lutheran |

Theoethot. |

Yes |

Competitive

inhibitory |

Strong |

Negative |

Yes |

|

Calvinism

|

Theoethot. |

Yes |

Competitive

inhibitory |

Strong |

Negative |

Yes |

|

Mazdeism |

Theoethot. |

Yes |

* |

Strong |

Negative |

* |

|

Islamic |

Theoethot. |

Yes |

Inhibitory |

Strong |

Negative |

Yes |

|

Class

C |

|

No* |

|

|

|

|

|

Dobu |

Anti religious |

|

Competitive

suspicious |

Yes* |

Negative |

Strong |

|

Kwaktiutl |

Anti religious |

|

Competitive

dionysiac |

Yes* |

|

Strong |

*This value is not extensively

proved.

Tab.

1

In this direction we can survey with appropriateness the existence of particular

traits of individual and collective personality, by comparing theoethotomistic

and religious cultures in the psychoanalytic and psychiatric description of

the so-called “religious” psychopathologies. From the Giacomo Dacquino

work entitled Religiosità e Psicanalisi[10] we mediate the definitions

of “religious psychopathology” and “sane religiosity” that through a new formulation

of “religious immaturity” and in correlation with the new idea of theoethotomies,

identifies in this one, pathologic forms of anal, oral and phallic religiosity

together with some important manifestations of religious neurosis. Schemes of

religiosity known as narcissistic, dependent, masochistic, hypomaniac, also

refer to this last one bringing back to the same manifestations all the types

of neurotic atheism, conscious and unconscious, as well as the most famous cases

of neurotic conversion [11].

The empiric test is based on data drawn from DSM IV Axis II; here are listed

mental disorders more likely led to the characters object of psychopathogenous

influence of religious model. The most important are: the schizotypical disorder

of personality, the paranoiac and the dependent one.

In some cases, for example, the disorder is characterized by the great emphasis

attached to the militant sense of religious belonging, or by an attitude of

passivity and deference in comparison with the sphere of the Holy; other cultures

encourage in different way a dependent attitude. These troubles of personality

tend to reveal themselves also through an excessive worry about lack of order,

a tendency for some form of perfectionism and mental or interpersonal control

in spite of flexibility, opening and efficiency. In a cultural system not so

far from us, following an interpretative line referred to the studies of Max

Weber[12], a special emphasis is attributed to work and productivity, two elements

here projected or intended in a sacral dimension; in these cultures these mental

schemes and relevant attitudes are obviously not considered pathologic.

As far as the sense of guilt is concerned (as formal and unequivocal lynch-pin

of the integration of the religious sphere in the moral one, according the permeating

modality typical of theoethotomistic contexts), we follow the Dacquino’s purpose,

where the origin of a conscious or unconscious sense of guilt is connected with

the sentiment that in the first years of life allows the individual to form

moral categories of the Good and Bad, either through gustative, or motion or

acting experiences.

Individual maturation should occur according to schemes leading to an autonomous

and authentic adult phase, where individual can interpret some mature needs

of the Super Ego. During the adolescence through the Super Ego is expressed

a necessity developed «(…) just from an encounter among the

irrational unconscious impulses and the precept imposed by external authority

(parents and educators)»[13]; during the full development process

of the Super Ego, it becomes representative of «an important dynamic

element of individual evolution because, apart from checking the emotional needs

(…), it meets the interior ideal of the Self (...). So the Super Ego rules,

got part of inner life, take part not only in the individual psychological evolution,

but also in his moralization, in his social life»[14].

A sane maturation, consisting of a mechanism which tends to absorb the Super

Ego and its immature needs formed in the early age, represents a psychological

and ontological objective that individual cannot realize if placed in a theoethotomistic

dimension, where the dogmatic imperatives resulting from the rules set by divinity

appear continuously in front of him. Ethical model proposed in these systems

fixes the individual Super Ego to an intrusive and irreducible stage, since

the Bad is not only a simple primordial metaphysical principle, just as can

be found in the myth and in religious folklore typical of the most pre-permanent

polytheistic cultures, but it becomes an essential element pervading the individual

ethical sphere, broadly present in the daily dimension, source of an everlasting

tearing interior conflict, impregnating individual attitudes with sense of unworthiness,

inadequacy and frustration compared with an infallible authority.

On the contrary in a religious context, where there is no place for a sense

of guilt since all the repressive activities are not irrevocably crystallized,

individual can rely on a precious irreplaceable help for getting an adult condition

objectively sane, without immature aspirations but following some stabilizing

dynamics of development (see fig. 1).

Fig.

1

In

the Genesis, especially according to the psycho-sociological interpretation

given in Metamorfosi della Ragione[15], an immediate consequence of

the knowledge of the Good and Bad is just the acquisition of a sense of shame,

connected with the conscience of nakedness. This makes as clear as ever the

relation between metaphysical cultural dimension and some important deep psycho-sexual

manifestations, often pathologic, frequent in the human nature.

Given the special origin of the Ideal of the Ego in a theoethotomistic model,

the development of Super Ego and behavioral practice, that are following the

necessity to lead the Ego to a continuos mediation between the conflicting needs

of Super Ego and Es, are “witness” of socio-cultural conditions and, then, of

a psychical reality that can be preceding serious psychopathologies characterized,

according to a psycho-analytic language, by fixations and pre-genital regressions.

Cultures inspired from religious models seem on the contrary able to distinguish

development “normal” and “sane” personalities, according to the typical pathologies

ascribed to this cultural dimension; they transmit social and cultural expressions

that hinder psychopathologic deviations to rise up, and are a premise of an

authentically autonomous development of an adult personality.

Our work proposes an interpretation rich in socio-cultural implications, since

during the historical process towards the affirmation of a standing civilization,

agricultural practices, social structure according to the hierarchic principle

and the state-authority, the definition of an ethical weighty entity has occupied

a very special place. According to our thesis here presented, that evolution

seems to have heavily marked individuals and groups history, and to have started

in western civilization a process towards a progressive stiffening in collective

and individual psychological structure.

We open a revisional perspective, from an evolutionist point of view, for traditional

ideas “normality” and “illness”, so a radical re-statement of the idea of mental

disease. In this direction hypertrophied Super Ego and edipical dynamics are

no more incurable features or factors of psychological nature of human personality;

they roughly represent contingent solutions, structured according a particular

level of individual development or collective conscience.

Starting from our hypothesis of a connection between some special shaping and

functioning mechanisms of human brain and cultural evolution process – i. e.

religious –, we attribute a great importance to the formal distinction between

1) societies where the notion of authority is central – i. e. where a remarkable

ethical merit content is typical of the ultramundane dimension – and 2) “primitive”

societies, interested by some “natural” religious expressions. We then analyze

the correspondence between individual free choice and behavioural model proposed

by the culture to which an individual belongs. From this perspective we draw

some interesting points of reflection about cases of collective adaptation dynamics,

or the psychological “anomaly” as a product of the discordance between natural

inclinations and group’s behavioral expectations and about the origin of uneasiness

of contemporary individual. It follows a critical opinion on the typical “diseases”

of our society and on the border sharing normality and deviation.

The question in hand suggests a search line involving some new discriminants

about a questionable angle of traditional psychopathological analysis, and finds

a relational link between the new meaning we attribute to the sacred dimension

and the most innovative development in the present-day psychology.

[1] F. Petrelli,

R. Verolini

e L. Venturi,

Neuroscienze ed evoluzionismo per una

concezione olistica delle psicopatologie e dei disturbi della personalità,

Camerino, Università di Camerino, 2000.

[2] R. Verolini e F. Petrelli, Metamorfosi della

Ragione: esegesi evoluzionistico psicosociologica di Genesi 1,3 e implicazioni

bioetiche, Camerino, Università

di Camerino, 1994.

[3] R. Verolini,

Il Dio laico: caos e libertà, Roma,

Armando, 1999.

[4] As from this point, all

terms based on the root «religio»,

written in italics, are intended in a meaning unlike the habitual; they specifically

denote those theological systems marked by the presence of non moral divinity,

or where we point out a concept of sin which could not be taken back to the

peculiar beliefs of the occidental culture.

[5] L. Braconi,

Personalità: eredità e ambiente,

Milano, Rizzoli, 1972; C. Holden,

The genetics of personality, «Science»,

n. 237, agosto 1987, pp. 598 e segg.; N.

Galli, L’educazione sessuale

nell’età evolutiva, Milano, Vita e Pensiero, 1994, pp. 23-66; S.

H. Washburn, Vita sociale dell’uomo preistorico, Milano, Rizzoli, 1971, in «A/P

Antropologia-Psicologia», Bollettino del Seminario “Biologia e Cultura”, nn.

1-2, 1994, p. 4.

[6] G. Corbellini,

Teorie immunologiche e darwinismo,

«Le scienze», n. 348, agosto 1997, pp. 52-58; G. M. Edelman, Sulla materia

della mente, Milano, Adelphi, 1993; ID., Darwinismo neurale: la teoria della selezione dei gruppi neuronali,

Torino, Einaudi, 1995, p. 19; ID., Il

presente ricordato. Una teoria biologica della coscienza, Milano, Rizzoli,

1991.

[7] M. Brillant e

R. Aigrain (a cura di N. Bussi

e P. Rossano), Storia delle religioni,

Alba, Edizioni Paoline, 1970; R. Biasiutti,

Razze e popoli della Terra, Torino,

UTET, 1967; M. Harris, Antropologia

Culturale, Bologna, Zanichelli, 1990.

[8] Verolini e

Petrelli, op. cit..

[9] E. Fromm, Anatomia

dell’aggressività umana, Milano, Mondadori,

1975.

[10] G. Dacquino,

Religiosità e Psicoanalisi, Torino,

SEI, 1980.

[11] ID.,

op. cit., pp. 119–208.

[12] M.

Weber, L’etica protestante

e lo spirito del capitalismo, Firenze, Sansoni, 1965; ID., Le

sette e lo spirito del capitalismo, Milano, Rizzoli, 1977.

[13] ID., op. cit., p. 230.

[14] ID., op. cit., pp. 230–231.

[15] Verolini e

Petrelli, op. cit..